- Home

- Kim Fields

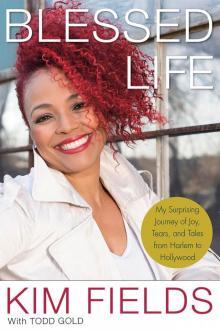

Blessed Life Page 13

Blessed Life Read online

Page 13

To mitigate my nervousness, I called myself Blondielocks. Even with that pen name, I was still Kim, and I was still shaking from the inside out. What I said was not anything a writer gave me. Those lines were my thoughts, my creativity, my soul, and oh my God, I might as well have walked onstage butt naked. I could not have felt more exposed. In the intro to one of her songs, my dear sisterfriend Erykah Badu said, “I’m an artist, and I’m sensitive about my *##%.” It was one of the greatest, truest lines I had ever heard, and it described the way I felt as I recited a piece called “Exotic or Toxic.”

Exotic or toxic

Which will you be?

To my mind,

My body, my soul,

To me?

Exotic or toxic?

Exotic like a faraway land,

Like Never-Never Land…

Or toxic like a man who is still a boy,

Like Peter Pan?

It was an exploration of all those questions you ask when you meet a man who jump-starts your heart. My recitation was a performance. It may have seemed like I was doing a character, but it was actually me; a part of me came out when I spit my words. Intense, passionate, dramatic, angry, soft, I took the audience—and myself—for a ride, especially with this one, which reopened some old wounds. After several minutes, I came to an abrupt stop. “Exotic or toxic?”

I lowered my head and stared at the rug covering the hard boards of the stage. I closed my eyes. I took a deep breath, which felt like the first one I had taken in a week. Then, from within the faraway place I had gone to recover, I heard a noise—applause. Ah, sweet applause, the lifeblood of a performer. The response was fantastic. I looked up, smiling, and had my Sally Field moment where, feeling relief and satisfaction, I thought, They like it. They really like it.

And they liked me. Imagine that. Drink that in, sister. This was not Tootie they were clapping for. Nor was it Regine. I didn’t recite lines from their writers. It was me, Kim, performing my words…channeling my poet world, and wow, they liked me. They really liked me.

After that I dove in headfirst. I wrote nonstop and read as often as I could. I had to buy another journal and soon, another one. Emboldened, I had a longtime guy friend in Chicago whom I looked at one night when we were out having dinner and wondered aloud, “What do you think a romantic version of us would look like?” I do not think I would have had the nerve to go there if not for the poetry. We tried it. He gave me a beautiful crystal vase, which I filled with flowers.

A week later, we started to realize that romantic territory was not a good fit for us, and lo and behold, the vase he gave me broke. Instead of cleaning up the mess, I ran for my journal. That night I stepped onstage at a club out in the suburbs. It was another open mic night. He was in the audience and heard me read this brand-new piece I had titled, “The Vase You Gave Me Broke Last Night, Is It a Sign?”

Heart and soul were just talking about you the other day,

wondering if there would be a sign, and then the vase

you gave me broke.

As I sat back down at our table, he shook his head in what appeared to be admiration. It could also have been amusement. A waitress brought me a glass of water and complimented my piece. After she left, my friend gave my hand an affectionate squeeze. “You’re so deep,” he said, smiling. “And, no, it wasn’t a sign.”

* * *

Following the play, I kept busy with cameos on various sitcoms. I also spent three glorious weeks in San Francisco for Me & Mrs. Jones, an indie feature that was a vitamin shake for my ego. Described by Variety as “a mix of romantic comedy and boss-from-hell shenanigans,” and costarring Brian White and Wanda Christine, it was about a hot young graphic artist (Brian) at an online dating service whose boss (Wanda) takes an interest in him, and vice versa, until Mr. Hot Stuff comes upon my flashy self. The director Ed Laborde specifically asked for me. I was ecstatic to be tapped for a part that framed my thirty-two-year-old behind as desirable—er, irresistible.

I ate it up. I was a leading lady. I was also in a movie that was not a stereotypical “black” story. Movies like Love & Basketball, Waiting to Exhale, Eve’s Bayou, anything from Spike Lee, and Me & Mrs. Jones showed there were many meaningful, profound, romantic, dramatic, and lovely human stories to tell featuring African Americans. There just weren’t enough of them—not in theaters or on TV.

The issue was a personal one. I had spent fifteen years on TV and I benefited from name recognition. I never felt anything less than loved, but rarely did I feel wanted by the industry where I had spent half my life. Why else was I not working more often? How else could I explain that I was not auditioning for comedies about black families or being called in to play a doctor on a new hospital drama? The fact was, Hollywood just didn’t have enough jobs for black people. Not for me—and not for any of the other actors, writers, producers, and directors of color.

That was one of the motivations behind the production company I’d started. I wanted to create roles for actors like me. I wanted to tell stories that were going untold. Only in retrospect did I see the obstacles were greater than I imagined and more powerful than little ol’ me could overcome. But that did not mean I gave up. I was still here—still looking, fighting, and kicking. Still scrappy. I told myself there was a cycle. You finish a series, then you have a small drought, then there is a whole bunch of guest-starring work, and then another series comes along. I imagined that I was in the guest-starring phase before that next big thing came along.

The system, like society itself, was weighted to squeeze the self-worth we had as African Americans. I refused to accept it. Maybe it was because I was older, more confident, and more determined, but instead of retreating to my bedroom as I had before, I continued to create. Work was my way of fighting back. I directed the Nickelodeon series Taina and an issue-oriented syndicated daytime series called Teen Talk. I worked on an indie film in New York until financing fell through at the tenth hour. I did another play in Detroit.

But the most satisfying work I did at the time continued to be my spoken word, which I took to smooth jazz festivals. I did festivals in Mexico and the Bahamas. I went back to St. Lucia. I opened for trumpeter Rick Braun. Working the stage in front of my band, my thing was part performance, part therapy, and part primal rant. I’m still here. I ain’t going anywhere. I’m still creating. You will not lock me out or shut me up. I am better than ever. In fact, when you look at me, you’ll see what I see: there’s more of me to be. More of me to be.

Perhaps this line of thinking was my version of a sentiment to come forth years later in the hit musical Hamilton, with the song “The Room Where It Happens.” I sat riveted throughout the show, and when I heard that song, all I could think was, If I’m not in the room where it happens, I’ll make my own room where it happens.

* * *

Indeed. In 2003, I collaborated with singer-trumpeter Johnny Britt and rapper-singer Sean E. Mac, better known as the smooth jazz–hip hop duo Impromp2, on a cut about a fictional spoken-word poet who went by the name of Mocha Soul. “Mocha Soul, that’s me,” I purred. “Speakin’ my truth into the wind, I’m finally comfortable in my skin…” I was supposed to be creating a character, but I couldn’t hold back the autobiography. I poured a lot of myself into it, and as I did, unavoidably, I began to think about cutting my own album.

It seemed like a daunting project until inspiration hit. I was in IKEA of all places, looking for a side table. As I walked from the area with living room furniture into the section with accent pieces, I had a vision—an ecstatic vision like none other in my experience. I saw the album almost in its entirety, complete and whole, right in front of me. It was just there, as in front of me as the storage unit I grabbed hold of to steady myself. I grabbed one of those little yellow pencils and a handful of small notepads they provide to write on and I practically wrote the entire album that eventually became Smooth Is Spoken Here.

Crazy, right?

Soon I was in the studio with

musician friends. I did not write music, but I was able to communicate the sounds I heard in my head to the great players I worked with, and they turned those rhythmic musings into eleven tracks, including “Playtime,” “Swanky,” “HarlemHoney,” “The Cool-Out Spot,” and “Smooth Is Spoken Here.” My dear friend, superstar saxohonist Najee and poet C.O.C.O. Brown were among those who generously added their gifts. And yes, the album had a definite vibe, which one New York paper called “a dynamic collaboration of music and poetry.” Thank you.

A limited run of CDs were made and sold through Carol’s Daughter, the online retail store founded by our family friend Lisa Price, and on my own website. When the CDs were gone, they were gone—that was it. For me, it was enough to have made the album. But I continued to tour and share my spoken-word poetry. In 2005, I went on HBO’s Russell Simmons Def Poetry Jam. I had been a fan of the show since its debut in 2002 and applauded HBO for putting it on the air. Though purists criticized the show, I was in from the debut episode. It put amazing poets and spoken word artists in front of a broad audience and gave us a podium on which we could stand and speak freely of every aspect of our lives. Where else could you hear Nikki Giovanni, Georgia Me, and Sonia Sanchez? These were our voices, and not watered down by a network’s commercial sensibilities and needs. I mean the fourth episode featured Dave Chappelle and Amiri Baraka reading his powerful piece “Why Is We Americans?”

This was powerful stuff. Just WOW stuff.

He was speaking to us—and for us.

And it was on TV!

By the time I went on the show, I was aware of the high bar that had been set. I worked out my piece at the Conga Room in LA. It was titled “How Come? (War Cry of the Single Woman)” and it was a big, sprawling, angry, reflective work meant to challenge myself as much as it did those on the receiving end. I flew to New York and went onstage draped in a beautiful, floor-length green and gold dress, with my blond locks and swag fully on. I glared at the audience just long enough for them to get the message that they weren’t about to hear Tootie or Regine. Then I started:

HOW COME? (War Cry of the Single Woman)

Well maybe it’s not you, it’s them

Maybe they’re scared

Maybe they’re intimidated

Maybe they’re gun-shy

Maybe I’m tired of them crutches,

Weak excuses, but too scared to grab a gun and fire!

HOW COME

I can cook my butt off,

talk cars,

sports,

politics

wax it with passion,

yo,

and still single?

Will cook catfish naked in high heels

and love like a champ,

give them fever…

HOW COME

“Oh well baby, you too good for me.

Uh baby, I don’t deserve you.”

Don’t settle for that come up.

Step up.

HOW COME

You respond with,

“You trying to change me?”

HOW COME

You weren’t ready and wanted to “just be friends”

when I perfectly rolled a tree on the first try

because I heard you say that’s the sexiest thing a sister

could do for her man?

HOW COME

You don’t realize and don’t remember that the King

Is supposed to be with the Queen,

Not the court jester?

HOW COME

I heard that after 9/11 folks got more committed to life,

love, spirit, family?

Are we saying that tragedy and fear should jump-start the heart?

We mustn’t forget these classic crutches

and excuses:

“Uh, I had a messed up childhood” (who hasn’t?)

“Uh, well I’ve been hurt real bad” (who hasn’t?)

“Oh, well, baby, you know what, baby, you see the time is not right,

see the time is not right,

see I wanna be in a certain place

financially,

emotionally,

spiritually.”

“Yeah, well, baby, most people are divorced,

and if they are together they ain’t happy.”

So?

And?

Have we forgotten y’all that once upon a time

high school sweethearts who met in third grade

got married and they built a life

and shared a life

and set and met goals

and loved with souls

Is that a fairy tale lived long ago?

I don’t know.

How far away from that do we go to get back to that?

Because you know

History does repeat itself

HOW COME

we can’t meet each other in the middle

with our fears and our hang-ups and our issues?

HOW COME

We can’t meet each other in the middle

And live and love

And live and love

And live and love?

HOW COME?

That Still, Small Voice

17

Get in the Passenger Seat

and Let God Drive

I remember when “How Come” first came out of me. It was a few months before I performed it on Def Poetry Jam. I sat on my bedroom floor, exhausted from shouting and crying those words into my little recorder. I had recently ended a two-year relationship for which I’d had oh-so-high hopes. The two of us were not able to get on the same page in terms of having life goals and a family together. It had been a painful last conversation for both of us; my spirit was so heavy and my heart was still wounded. With my face buried in my hands, I asked, “How come it didn’t work out?”

I was speaking specifically—and generally.

I was speaking for myself. I was speaking for so many others.

It was light outside, the late afternoon. I walked outside and looked around the backyard. My gaze fell upon a neighbor’s jacaranda tree. Its branches rose above the fence. Full of leaves and purple flowers, it looked like the kind of impressionist tree Monet would have created had he lived in LA. It was beautiful. I did not want to carry around the heaviness of a wounded heart. I remember being on the phone with a girlfriend and saying, “I’m over it. Done with it.”

Such outbursts were uncharacteristic, but I needed to vent. “He wasn’t the one,” I continued. “Neither was the other guy. I don’t get it. I’m not a crazy chick. I’m not one of those women about whom people say, ‘Oh, watch out for her.’ Maybe I’m just part of a generation that has some bad women who screwed it up for those of us who are good. That’s it. There are bad women out there messing it up for us good ones.”

My friend laughed. “You sound like you’re spittin’ on Def Poetry again,” she said.

I summoned a half-smile. “I’m definitely spittin’,” I said.

Ready to start building something and willing to shake things up, I put my house up for sale and began traveling to Tampa, Florida, intending to purchase five or ten acres. Land was cheap there, cheaper than in LA. I wanted to build a house—or an ark. Or something. I had no intention of giving up acting, directing, or producing, but my agenda now included other goals.

Like opening a juice bar. Why not? I figured I would write my next TV series there, too. And if I met a man, well, I had mixed feelings about another relationship, obviously, and would deal with the situation when and if it happened.

But one thing stood above all else. It was more of a question than an actual objective, and the question was this: What about kids? I had asked that question before, when I was in a relationship, and it seemed more feasible. Now, in my midthirties, I wanted certain parts of my life fulfilled, and having children was on my list. It was, in fact, high up on my list. I never subscribed to the ticking biological clock. I trusted that God knew my heart. I wanted my Partner in Life &

Love…I wanted Husband. I wanted to be Wife. I wasn’t rocking rose-colored glasses. I didn’t simply want the roles or labels. I also wanted the work that came with them.

One day I was having lunch with my friend, music producer Carvin Haggins, and though I was seated across a small table, he could see my mind was elsewhere. Apparently I had muttered something as he was talking to me. “I was thinking about children,” I said. “Let’s say I don’t meet anyone and I want to have a baby—or babies—on my own. How do I even go about it? Do I make a short list of my male friends whom I love and adore and tell ’em, ‘Hey, no strings attached’? Or do I adopt?”

Carvin sat back and rubbed his chin in thought. We talked about dating and relationships, before moving the conversation onto other topics. He had several projects. I’d been on several auditions. “My foot is on the gas,” I said, “but the car is still in neutral.” He sympathized. Show business is a collaborative business, requiring many people at different levels to buy into a project before it gets off the ground, which is sort of like everything in life.

I sighed. Carvin reminded me that Jesus was thwarted time and again. I nodded and repeated something that Pastor Joel Osteen had once said: “Hang on to your faith. It may not look like there’s a way, but God still has a way.” And that is essentially what Carvin told me. He said, “Kim, my friend, get back in the passenger seat and let God drive the car.”

I got it.

Take a deep breath.

Loosen your grip.

Let life happen.

Then be ready when it does happen.

* * *

And so I was.

It was April 2005, and I had sold my house, put my belongings in storage, and moved in with my mom and dad. I did not like the idea of moving in with my parents at age thirty-six, but my monthly jaunts to Florida and side trips to New York, Chicago, and Detroit for work and appearances or meetings ensured I was more of a visitor than a semipermanent squatter. On the plus side, they were a supportive cheering section. When I booked a pilot for a sitcom based on the rapper Bow Wow and his mother, my mom and I jumped up and down, hugged, and hollered the way we did in 1976 after I booked my Mrs. Butterworth’s commercial (and every time since). It was the way we were and would always be.

Blessed Life

Blessed Life